In which we follow a money trail—and ask

whose it is

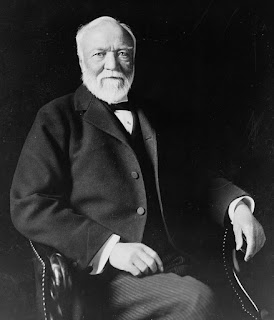

So, gang, what did you make of that Andrew

Carnegie reading on the Gospel of Wealth? Let me read the key paragraph again:

This, then, is held to be the duty

of the man of wealth: To set an example of modest, unostentatious living,

shunning display or extravagance; to provide moderately for the legitimate

wants of those dependent upon him; and, after doing so, to consider all surplus

revenues which come to him simply as trust funds, which he is called upon to

administer, and strictly bound as a matter of duty to administer in the manner

which, in his judgment, is best calculated to produce the most beneficial

results for the community-the man of wealth thus becoming the mere trustee and

agent for his poorer brethren, bringing to their service his superior wisdom,

experience, and ability to administer, doing for them better than they would or

could do for themselves.

—Sounds like Carnegie sees himself as the

ultimate American Dream boy.

Explain what you mean, Ethan.

—I mean he sees himself as someone who starts

with nothing, works hard and becomes rich.

—And screws everyone else in the process.

Everyone else, Brianna?

—OK. Maybe not everyone else.

But a lot of people. Look at what he did at his factory at Homestead, locking

out those workers. That was cold.

—OK. Maybe not everyone else.

But a lot of people. Look at what he did at his factory at Homestead, locking

out those workers. That was cold.

Well yes, there was some unpleasantness there.

But let’s not dwell on that now, shall we? We don’t want to end up sounding

like that horrid little man Eugene Debs, who has such peculiar ideas about the

relationship between capital and labor.

—Yeah: that the workers make the

capital.

Again: let’s talk about something more

pleasant, shall we? Like charity, Carnegie style.

—You keep saying Car-nay-gee. Is that the right

way to pronounce it?

Yes, Kylie. Like Henry David Thorr-Row.”

—Weird.

Maybe so. Anyway, as you know, Carnegie

becomes the dominant figure in the new American Steel business in the closing

decades of the 19th century. Which puts him right smack in the

middle of the Industrial Revolution. Because steel is absolutely crucial. A

man-made material derived from iron—like oil, it has to be refined before it

can be a useable fuel, iron must be manipulated at very high temperatures to

become steel. Once you do that, though, it has all kinds of uses. It’s

indispensable in the railroad business, for example. Steel is to the Industrial

Revolution what fiber optic cable is to the Internet. You don’t always see it

behind the walls, but you’re nowhere unless it’s there.

—Isn’t it also used in buildings?

Indeed it is, Kylie. The fact that steel is

both incredibly strong and relatively light makes it possible to erect really

tall buildings in cities like New York and Chicago. Steel is so important, in

fact, that it becomes a measure of a nation’s industrial prowess—a

nation’s place in the global pecking order was often ranked in terms of its

steel production. That was true well into the 20th century,

when the leader of China, Mao Tse Tung, starved his own people in a mad quest

to boost steel production in an initiative known as the Great Leap Forward. But

that’s another story. The point is that Carnegie becomes a very rich man making

steel, and becomes richer still when he sells his business to banker J.P.

Morgan for something like a billion dollars.

—Pocket change.

Maybe so, Emily. But one thing you can do with

that kind of money is charity. And Mr. Carnegie is a charitable man. But he’s

not content to simply give the money away. He thinks it’s important to help

people to help themselves.

—Give a man a fish, blah blah blah.

Just so. So Carnegie makes an offer to

communities around the country. He says that education was the key to his

success, and that the key to his education was public libraries. That’s why he

offers—and in fact he does—build hundreds of libraries and stocks them with

books. But he has a condition: the communities that receive these gifts must

promise to maintain these libraries and staff them appropriately. My question

is: Does this seem like a good deal?

—Well sure. I mean, why not?

—Jonah’s right. After all, it’s his money.

Hmmm. His money. But is it, Chris?

—Well, yeah. He earned it, didn’t he?

Well, I don’t know, Chris. What do you mean by

“earn?”

—Right. He didn’t earn it. He stole it.

—Oh, c’mon, Brianna. It was his company. The

whole thing was his idea. I mean, yes, he had people do work for him. But

without him, the company would have never happened. He was a talented guy. And

a guy who created jobs.