In which we see one man die, but nobody win—though a nation survives

—OK, Mr. K. It’s time for that happy ending.

What happy ending, Kylie?

—The one you said was coming. With Thomas Jefferson as president.

Did I say it was going to be a happy ending?

—Whatever, Mr. K. Just get on with it.

Yes, ma’am. Thomas Jefferson is re-elected, handily, in 1804. But things are beginning to get rocky again.

—Why?

Let’s go back to Aaron Burr. Also known as the Vice President of the United States, which is what he became after his failed attempt to seize the presidency from Jefferson in 1800.

—Yeah: whatever became of him?

Iceman. After what happened, Jefferson didn’t want to have anything to do with him. Burr was completely frozen out. And it was absolutely clear Jefferson wouldn’t have him aboard for his second term.

—Not surprising.

No. So Burr went back to New York, and ran for governor. He lost—thanks to his old frenemy Alexander Hamilton, who mounted a successful effort to stop him. Hamilton was mad at Burr for having snatched a senate seat from his father-in-law a few years earlier. Their contempt is now mutual and open. And then Hamilton says something about Burr.

—What?

It’s not clear what. Something critical. Burr hears about it third-hand, and sends a note to Hamilton demanding he apologize. Hamilton refuses. The feud escalates. And then Burr challenges Hamilton to a duel.

—You mean like with guns?

Pistols. Dueling is an old tradition, and one that had been common in the United States, especially in the South. (We’ll hear about it again when we talk about Andrew Jackson.) But it was fading a bit up North, and had become illegal in some states, New York among them. But people were still doing it, and among them Hamilton’s own son, who was killed in a duel in 1801.

- Alexander Hamilton

Hamilton didn’t want to duel Burr. But he felt he had no choice: he wasn’t going to back down to a scoundrel. Some people thought Hamilton had become a scoundrel by 1804. He had schemed, twice, to deprive his presumably Federalist ally, John Adams, of the presidency. He failed the first time, but the second, in which he published a pamphlet attacking Adams, may have played a role in Adams’s defeat (it certainly hurt Hamilton’s reputation). Much worse were rumors that Hamilton had abused his powers as Secretary of Treasury, rumors that arose after reports surfaced that he had used government money to pay bribes to a shadowy figure in Philadelphia society named James Reynolds. Faced with exposure, Hamilton wrote a different pamphlet in which he said, yes he had paid bribes, but with his own money—not because he was guilty of financial fraud, but because he was being blackmailed by Reynolds for adultery by with his wife, Maria Reynolds. In effect, he sacrificed his private reputation (and his wife’s feelings) to save his public reputation. So now we have a duel between a disgraced former Secretary of Treasury by a disgraced Vice President.

—Jesus.

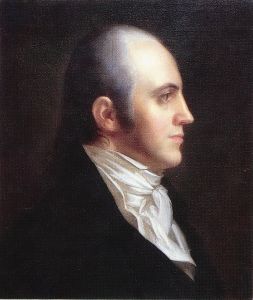

- Aaron Burr

illegal in New York, Burr and Hamilton row across the Hudson River to Weehawken, New Jersey in the early morning hours of July 11, 1804. Hamilton, who at some level can’t quite believe this is happening, fires his shot in the air over Burr’s head. Not Burr: he shoots Hamilton in the gut. Hamilton takes two days to die. Once he does, Burr is wanted for murder in New Jersey.

—Jesus!

Ethan, I thought we agreed—

—Sorry.

—So what becomes of Burr?

He’s a fugitive from justice, wanted for murder in New Jersey. He also knows he has no future in Washington. He flees the country and hatches a plot with the Spanish government to found a new American republic in the neighborhood contemporary Arkansas.

—Jes—just kidding. Does it work?

No, Chris. Burr gets betrayed by one of his collaborators, James Wilkinson, a revolutionary war vet with a history of shadowy collaboration against General Washington. But after working with Burr for a while, Wilkinson gets cold feet and blows the whistle on Burr. He’s arrested and dragged back to Washington to be tried for treason. His treason trial is presided over by John Marshall, the chief justice of the Supreme Court. Marshall was appointed by Adams on his way out the door along with a bunch of other judges, which infuriated Jefferson. Marshall would run the court for 35 years, and turn it into a bastion of Federalist power. Oh, and one other thing: Marshall is related to Jefferson (they’re distant cousins). They loathe each other.

Jefferson really wants to stick it to Burr. But Marshall really wants to stick it to Jefferson. He does it with a rule that proves lastingly influential: Marshall insists that charges against an individual need to be corroborated by more than one source. Anything short of two is hearsay. There’s not enough evidence against Burr, who’s acquitted in 1807 (he goes on to live for another 29 years).

—I kinda can’t believe we had such a crazy country. Leaders killing each other, conspiracies to form alternative countries, crazy elections. You hear about these things in other places. But I didn’t know it happened here.

Right, Sadie. That’s exactly what I’ve been trying to emphasize these last few classes: that this is a country that had fragile beginnings. Every country always has intrigue. But the key point, and it’s one I want to return to now, is that a lot of this fragility is rooted in the fact that the nation is not entirely in control of its own destiny. To be sure, there are power struggles within: we’ve just been talking about those. But remember: the backdrop here is the global struggle between France and Britain. And in Jefferson’s second term, it bursts open again.

—So no happy ending then.

No ending at all yet, Kylie. We have a war to get to.

—Definitely no happy ending.

Well, it depends who you ask.

—I say you ask the dead.

Well, they tend not to talk much. But it’s fair to ask.

Next: the dumbest war