In which we try to unravel one of the great riddles of American History

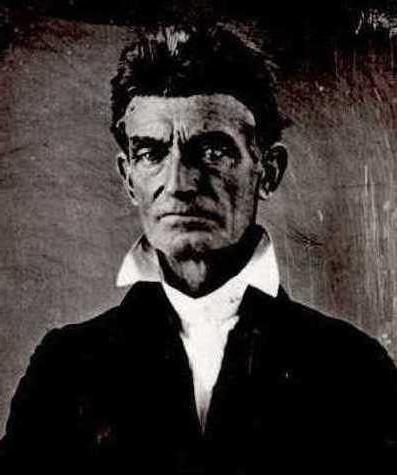

- John Brown

Kids, the facts of the situation are reasonably clear-cut. I’ll try and dispatch with them quickly.

By just about any standard of the last 150 years, John Brown is a first-class weirdo. You can see that from this picture.

—Those eyes! Totally creepy.

Agreed, Sadie. They don’t make ’em like they used to. Here’s Brown’s great ideological adversary, John Calhoun. You just don’t see faces like this anymore.

—Yikes! Brothers from another mother.

I don’t think they’d like that idea, Chris. Born in Connecticut, Brown spent most of his adult life wandering between western Massachusetts and Ohio. Brown, who married twice (his first wife died) and had well twenty children, has a rocky business record as a tanner.

—What’s a tanner?

- John Calhoun

—You’re right: he is a first class weirdo. Frightening.

Well, hold on, Kylie. Don’t make up your mind quite yet. In 1837, Brown learned of the murder of abolitionist Elijah Lovejoy in Illinois.

—Did we talk about that?

We did indeed, Yin. Good memory. From that point on, Brown became a dedicated abolitionist himself. Some—well, just about everybody—might say a fanatical abolitionist. By the 1840s, he was a good friend of Frederick Douglass, who had become internationally famous as the author of his autobiography as a slave. You may also recall that Brown was involved of the murder of proslavery advocates who were hacked together when they came out of that Kansas bar in 1856.

—We just did talk about that.

Right. All right, so to get to the point here: by the late 1850s, John Brown is hatching a plan. He wants to lead a slave insurrection. The idea goes like this: he’ll take 21 confederates, including three free blacks, one former slave, one fugitive slave, and three of his own sons, to a federal armory in Harper’s Ferry, Virginia (now West Virginia). They’ll seize control of the facility, and all the weapons stored there. When slaves see what he’s accomplished, they’ll storm in and he’ll arm them. This new liberation army will finally take the law into their own hands and bring about the real American Revolution. What do you say kids? Will it work?

—Insane.

—Won’t work.

—Not a good idea.

Well, not everyone agrees with you three. Brown has a group of elite Bostonians known as the Secret Six who are financing his operation. One of these people, Elias Howe, is married to Julia Ward Howe, who will later write “Battle Hymn of the Republic.” On the other hand, Frederick Douglass, who loves and admires Brown, declines an invitation to join him.

—So what happens? Or are you going to stretch this out and demand we tell you what happens?

Oh, Em. So jaded, so young.

—That’s me. I’ve become incredibly cynical. It’s what happens when you spend the better part of a semester with a crazy history teacher who makes you think too much.

Ah yes, the risks of a high school education. But no: I’m not going to string this out. The raid is a disaster. Well no—the raid itself is a big success. Brown and his crew take the armory easily (though in one of the ironies of history, the first person they kill is a black man). The problem is that Brown has no clue what to do once he actually takes control. He assumes the slaves will just come streaming down into Harper’s Ferry. But they don’t, perhaps because they recognize his plan as suicidal. Meanwhile, as he sits and waits, the U.S. army mobilizes to capture Brown. There’s an officer named Robert E. Lee who’s tasked with this job—

—The Robert E. Lee?

Yup. An engineer by training, he supervises an operation that literally tunnels under the armory and takes Brown and his crew by surprise. A bunch of them are killed, including two of Brown’s sons. Brown is captured, arrested, tried, convicted, sentenced to death.

—Well, you are getting to the point this time, Mr. K.

Told ya, Em. That’s because I want us to sort out what Brown has done. A minute ago, I asked you whether I thought the raid would work. A bunch of you said no. But let me pose a different question: was it a good idea?

—You mean even though it didn’t work?

Right, Kylie. I mean was it worth a try. What do you think?

—I’m not sure.

I’m shocked to year you say that.

—Look, I can understand why he might have wanted to do it. You have to hand it to the guy for his bravery. But it was still a dumb idea. He was dumb to think that the slaves would join him, and he was dumber to think it would solve the problem.

—I think it was pretty great.

—Really, Brianna? I mean, I get it: slavery is wrong, and ending it is key. But this was just plain counterproductive.

—Anything that attacks slavery is right as far as I’m concerned.

—The ends justify the means?

—Yes.

—I don’t know about the violence part. Even if you think killing is justified, I think it just might create a circle of violence. I just don’t know if that helps. I think Adam’s right.

—What do you think the Civil War did, Sadie? That solved the problem, didn’t it?

—But did it have to go that way, Brianna?

When John Brown was being executed, his dying words were, “I, John Brown, am now quite certain that the crimes of this guilty land can never be purged away but with blood.” He added that he “vainly flattered myself that without very much bloodshed, it might be done.” Brown thought violence was both inevitable and that he was actually trying to minimize it.

—Yeah, and he was insane.

—Are you insane to believe you have to do anything possible to end something as bad as slavery, Adam?

—Look, I don’t think it’s bad to be really committed. All I’m saying is that the way he’s going about it is a problem. I don’t think that makes me a racist.

—You wouldn’t talk that way if you were a slave.

—Maybe not.

—Here’s what bothers me: his big ego.

What do you mean, Em?

—It’s like, “Look at me! Here I am, Mr. Big White Guy coming in to save the slaves! Follow me!” No wonder nobody joined him.

—Twenty guys did join him, Em. Black guys and white guys. He put his ass on the line. He paid the price.

—I thought you were against what he did, Adam.

—Yeah. But Like I said, he was brave. I don’t think you should be dismissing that.

—Whatever. It’s still a bunch of guys. Throwing their weight around.

Where are you, Kylie? Any closer to an opinion?

—I still don’t know, Mr. K.

Pablo? Jonquil?

—I think he was hero. He took risks. It didn’t work out. But that doesn’t mean he was wrong.

—I agree with Pablo.

—I have a question.

Shoot, Yin.

—You’re asking us what we think. But how did people at the time react?

Well, as you might imagine, they were all over the map. And that map included indifference, though pretty much everybody knew what happened, because the raid was national news. Henry David Thoreau thought Brown was a great hero. (But of course many of the few people who were paying attention to him thought he was nuts, and had been for some time.) Virtually all white southerners were appalled by Brown’s raid, though some gave him grudging respect for the fearless way he went to his death. What may be more significant, though, is less how Southerners reacted than how they reacted to Northern reaction.

—What do you mean?

I mean, Sadie, that many of them were outraged about the lack of outrage. “Don’t you understand what he did?” they asked. “He incited the Negroes to murder us in our beds!” Here’s a guy who was avowedly promoting race war, and a lot of the criticism was of the Ethan variety: “um, not wise.” This event convinced some white southerners, slaveholding and not, that the North really didn’t care about them, and they would have to start defending themselves. Militias began to form, as in the Minuteman days.

By 1860, Sadie, a growing number of Americans began to believe that violence was really the only solution. Do you think they were wrong?

—I don’t know, Mr. K. But that makes me sad. I wish they were wrong. I hope they are wrong.

—What did your boyfriend, Abe Lincoln, think about all this?

Lincoln called Brown a man of “great courage” and “rare selfishness.” He also called him “insane.” Lincoln agrees with Sadie: violence is not necessary. He doesn’t even think it likely. He’s beginning to think he can fix the problem. It’s around this time he decides to run for president.

—Oooh. I wonder how that will go.

You’ll just have to wait to find out, Emily.

Next: the Railsplitter