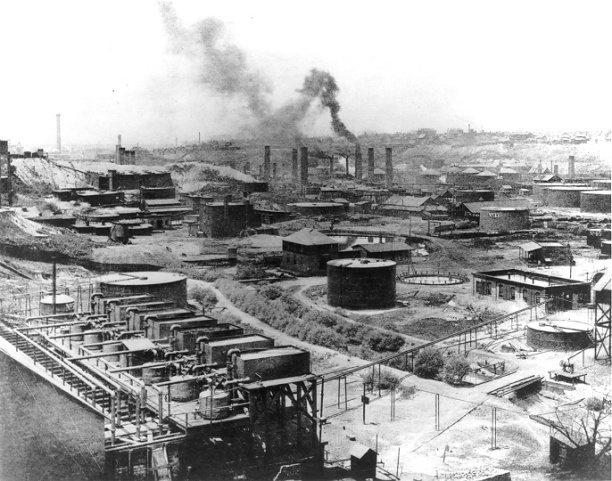

- Standard Oil refinery, Cleveland Ohio, 1889.

In which we see that free markets can be a complicated business

Ladies and gentlemen, I present to you the president of the Jonquil Railroad Company.

—Hey, nice job, Jonquil!

—Hey Jonquil, can I get me some free tickets to L.A.?

—Thank you. Thank you all. Jonah, that would be no.

—Awww. Really?

—Well, we’ll see.

You can be sure that Jonquil didn’t get to where she is by giving things away, Jonah. She’s a tough businesswoman. Actually, much of her clientele is oil companies. More specifically, her clients include Chris, Yin, Brianna, Kylie and myself. We all own companies that ship our product along a key stretch of her line that stretches from Chicago, Illinois, to Cleveland, Ohio—essentially across the bottom half of Michigan. Rail is a much more efficient means of transportation than the alternative, which involves shipping by barge around the Great Lakes. That’s what we used to do before Jonquil came along.

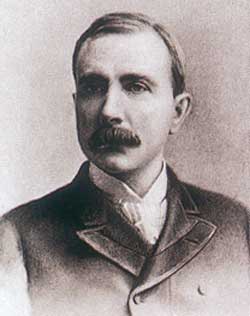

- John D. Rockefeller, 1875

Oh: I almost forgot to tell you. My name is John D. Rockefeller. I own a company called Standard Oil.

—Hmmm. That sounds vaguely familiar.

Well, I’m not very well known. I’ve really only been in business for a few years, since the War Between the States.

—Well, something tells me that you have a future, young man.

Why thank you, ma’am. As you may know, oil is a difficult trade. It’s really only been a business for a few years. Actually, the oil business itself only dates back to, 1859, when it was discovered that the thick, viscous sludge that accumulated in ponds around the Pennsylvania and the Midwest actually burns clean for fuel, and does so more cheaply than alternatives like whale oil or kerosene. Nowadays, we drill wells underground and tap the oil as it surges to the surface. But it still has to be refined, much in the way that iron has to be processed into steel.

Here’s another, bigger problem: oil is basically a commodity.

—What does that mean?

Well, even though it has to be manipulated to be usable, it’s widely regarded as a raw material, like coal, or lumber or milk or butter. Manufactured goods, especially ones that have patents, tend to be much more valuable. To be honest with you, there really isn’t much difference between the oil that I sell, or that which Brianna, Chris, Yin, or you do, Kylie. And we all have the same fixed costs. Let’s say, for the sake of argument, that it costs $1 to extract one barrel oil from the ground. And that it costs another dollar to refine it. And a third to ship it on Jonquil’s rail line between Chicago and Cleveland on her Sandusky line. The only thing we can really compete on is price.

—So what do you do then?

Why don’t you ask them?

—Yeah, Adam, why don’t you ask us?

—Fine, Chris. How much do you charge for your oil?

—Six dollars a barrel. Three bucks to make the oil, three bucks in profit.

—Well I only charge five dollars.

—Well aren’t you special, Kylie. I charge four.

You can see where this is headed, Adam. All of us undercutting each other. Brianna is charging $4. As a result, Yin is likely to charge $3.50. The profit margin will keep shrinking. And here’s the thing: stuff happens. Maybe one of Brianna’s boilers will break down and have to be replaced. Now she has a big repair bill. Maybe there will be a strike at Kylie’s plant, and the workers will want more money. There’s a danger that they’ll be selling the oil for less than it costs them to make it. These price wars will be ruinous. Maybe everybody but Yin will go broke, and then she’ll be the only person producing oil. What do you think will happen next?

—Oil for ten dollars a barrel.

Right. A huge surge in prices. And when Emily and Sadie see how obscenely wealthy Yin is becoming, they’ll enter the market and charge nine dollars, then eight, and pretty soon, the whole process will repeat itself. And poor Ethan and Jonah, who are just trying to heat their house or fuel their tractor, will be on a never-ending roller coaster ride. Crazy, isn’t it?

—Something tells me you have a solution, Mr. Rockefeller.

Well, as a matter of fact I do. I happen to have a little extra money on my hands. And I’ll tell you how I’ve used it. I’ve built new state-of-the-art storage facilities. I’ve also built links between my plant and Jonquil’s depot to make it extra easy for her to collect my oil for shipping. As Jonquil knows, I’m absolutely fanatical about making sure she gets paid in a timely way. What I’m saying, in short, is that I strive mightily to be a dream customer. Is that so, Jonquil?

—Oh yes. A dreamboat.

Excellent. I am so glad to hear that.

—Uh oh, Jonquil. Something’s coming.

You see, I’m a much better customer than Yin, whose facilities are really a bit of a pain for Jonquil to reach. And Kylie has had some financial problems, so she doesn’t always her bills on time. And I’m told that Brianna has been actively looking for alternatives to shipping with Brianna, whether in terms of encouraging other rail companies to start competing in the region or negotiating a better price for shipping by barge. It’s slower, but that doesn’t mean it can’t be cost-effective. But, I, as Jonquil just said, am a regular dreamboat.

—Here it comes.

Jonquil, I’m hoping we can revise our arrangement a little.

—Uh, OK. What do you have in mind?

Well, here’s what I’m thinking. In this market of great uncertainty, I think we should really commit to each other. I’m willing to contractually promise a steady stream of business with you, which will no doubt help with your own financial planning. And I’ll continue to maintain state-of-the-art facilities to make your job easier. In return, I’d like a little discount on the shipping, a kind of most-favored-customer deal.

—How much of a discount?

Doesn’t have to be much. Maybe something like ten cents, so you’ll charge me 90 cents but everyone else a dollar. But here’s the thing—a thing that matters a lot to me, but shouldn’t really matter to you. I want this to be our secret. In fact, I want you to be able to say, accurately, that you charge everybody the same price of a dollar. We’ll have that ten-cent discount come in the form of a rebate that you give me later. One more reason to take the deal. Will you?

—Don’t do it, Jonquil!

—Rockefeller is the devil!

I’m an honest businessman, Jonquil. And I’m not competing with you. Actually, I think of us as partners. Ask your friend Adam here what he thinks. I bet he’ll give you good advice.

—Honestly, Jonquil, I don’t think you have much to lose. Actually, I think Brianna, Kylie, Yin and Chris have more to worry about. I could be wrong.

—What happens if I say no, Mr. Rockefeller?

I don’t know, Jonquil. But I’m mighty curious about what Brianna is up to. She’s a smart woman. Maybe those rumors about alternative forms of transportation are true.

—Oh, all right. Whatever. I’ll take the deal.

—Jonquil!

—Sorry, B. I just don’t want to have to think so much!

Excellent, Jonquil. We have a deal. Now let me accelerate the pace of time a little and explain what happens. I price my oil at $2.95 a barrel. That’s a dollar to extract, a dollar to refine, 90 cents to Jonquil and a tiny profit of a nickel per barrel. But I’m not losing ground. The others, by contrast, can’t charge less three bucks and expect to stay in business. Assuming disaster doesn’t strike me—possible, but not likely, because as you know, I am very careful and shrewd—sooner or later they will die. And they know that.

—You’re disgusting, Mr. Rockefeller. You’re going to do that ten-dollar thing you just said was so bad.

No, Emily, I’m not. Actually, the first thing I’m going to do is go to our friend Kylie. Kylie, let’s agree: you’re not the world’s greatest accountant. You’ve had your problems paying your bills even before this happened. But I really respect your skills in prospecting, and I think you have a good future. So I’d like you to come work for me.

—Well, what if I don’t want to?

Hey, it’s a free country. Which is why, if you persist, I will exercise my own freedom and crush you.

—Well, since you put it that way, I guess I’m joining you.

Wonderful! I’ll take over your operations. I’m going to pay you more than you were making. And Jonquil will be thrilled, because she knows I’ll do a better job of paying my debts than you ever were. And now we’ll have twice as much $2.95 oil. Chris, you see where this is heading. You want to join a winning team?

—I guess.

Excellent! Brianna? Yin? What are the two of you talking about over there?

—We agreed to team up to fight you.

Oh, that’s very unfortunate. That’s very unfortunate for me, because it means a temporary loss in profits. And it’s unfortunate for you two as well. I’m going to price my oil at a dollar a barrel. I’m afraid you simply won’t be able to survive that. I will drive you out of business. I’ll price my oil at a penny a barrel if I have to. Hell, I’ll give it away, because I know I can absorb more pain than you can. Would you care to reconsider?

—Are you allowed to do that?

What wouldn’t I be, Sadie?

—Aren’t there rules against this kind of thing?

Rules? Of course not. For one thing, this whole oil business hasn’t really been around long enough for there to be such rules.

—Yeah, but isn’t what you’re doing a monopoly? Isn’t that wrong?

Wrong? Absolutely not. Listen: I’m doing everyone a favor here. I’m bringing order out of chaos.

—Well, what’s going to stop you from charging $100 a barrel?

For one thing, it’s a big country. There are lots of Kylies and Briannas out there who will try to undercut me if I get too greedy. (Actually, trying to outsmart them is what makes this fun. Why I hope to keep doing it.) And I don’t like the roller coaster any more than the Jonahs and Ethans out there. That’s why I’m going to price my oil at $6.50 a barrel—and keep it there as long as I can. Bring some predictability to the market. Stability. That’s what the business community needs. That’s what consumers need. That’s what we all need. Don’t you agree?

Don’t you?

—This reminds me of that conversation we had about Carnegie and his libraries. I mean, it was nice that he built them. But it isn’t really his job. The government should do it.

The government? That bunch of losers? They couldn’t govern their way out of a paper bag! Everybody knows that no one with a half a brain goes into government in this day and age.

—Well, maybe that should change.

You go ahead and dream. In the meantime, I’ve got a business to run.