In which we view a nation teetering on the edge, and pulling back (for the moment)

OK, kids. So I think we need to take a little stock of where we are in the United States of America in the Year of Our Lord 1850. Texas is securely in the Union as a slave state. The Mexican War is over. Gold has been discovered in the newly acquired territory of California. It appears that the manifest destiny of the nation is indeed to stretch from sea to shining sea, and amid a booming economy, there are efforts afoot to stitch it together with an transcontinental railroad. You might say things really couldn’t be better.

And yet the national mood is miserable. Tell me why.

—Because of slavery.

Yes, Jonah. But what about it?

—Well, people can’t agree on it.

Agree on what?

—Where it will go.

Yes: where it will go. You make a very important point. Where slavery is—and isn’t—is regarded as settled. The argument is over the future of slavery. Proslavery advocates are becoming more and more convinced that the peculiar institution, as it’s known, must expand, which is why they’re hatching schemes like taking over Cuba or founding a colony in Nicaragua. Antislavery activists are becoming more and more convinced that it must not. Both agree, largely implicitly, that if slavery stops growing it will die. There are also some curious tensions, contradictions, hypocrisies. As we discussed, proslavery advocates have long been suspicious of national government power for any reason except the protection of slavery, because they fear that power could be used to regulate or destroy it. Antislavery advocates have generally favored a stronger federal government, except when it comes to things like enforcing the return of fugitive slaves. The effect of all of this has been gridlock: it’s getting harder and harder to get anything done.

—Maybe we need a war.

Now Ethan, that’s really offensive. War talk is sensational and inappropriate. I demand that you apologize right now, young man.

—Are you serious?

—Really, Ethan. Don’t you know by now when Mr. K. is in drama mode?

I have no idea what Emily is talking about, Ethan, but I do apologize. I guess I just got carried away. It’s just that there’s been so much irresponsible talk lately. All the abolitionists on one side, fire-eaters on the other. People tend to forget that both sides are really minority voices. Most of us don’t care about slavery one way or another. We just want peace!

—Fire-eaters?

—Probably means proslavery people.

—Sounds like Harry Potter.

—Cool term.

—Cool fire-eaters. Brilliant, Jonah.

So what are we going to do, kids? How can we break the gridlock?

—I have no clue. But I have a hunch you’re about to tell us.

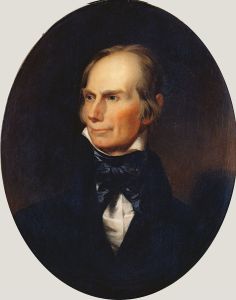

- Henry Clay

—Jeez, Mr. K. You’re obsessed with that guy.

Yeah, well, Em, a lot of us are. But in 1850, Henry Clay is an old man. He’s been dominant force in American politics for over forty years. He’s an antislavery slaveholder from agrarian Kentucky who seeks to promote the industrial revolution—

—That doesn’t make any sense.

What? You're confused by the notion of an agrarian industrialist?

—Nevermind that. Antislavery slaveholder?

Well, he’s not an abolitionist, for God’s sake, Em. Yes, he owns slaves. But he’s looking forward to the day when slavery is gone.

—What a hypocrite. How can you be for something and against something at the same time?

Kylie, are you an environmentalist?

—Me? Sure.

Then why are you drinking whatever that is from a plastic bottle? You say you’re in favor of saving the environment at the very moment you’re destroying the environment!

—Oh, c’mon, Mr. K. That’s unfair to Kylie. You’re being ridiculous.

Am I, Em? Or am I simply pointing out that people are complicated?

—No. You’re just being ridiculous.

So says a former supporter of Andrew Jackson. I know where you’re coming from Em.

—You are impossible.

Why thank you, Emily. Anyway, Henry Clay is old, and he’s dying, but he’s still a patriot. And he’s been thinking very hard about what might save the country from disintegrating. He’s put together an interlocking series of proposals known as the omnibus bill.

—What does omnibus mean?

—Isn’t it like a bus?

In a way, yes. “Omnibus” basically means multiple. Like kids on a school bus. The idea here is Clay’s bill consists of a set of proposed laws. If you vote in favor of it, you get the whole thing. It will have stuff you like, but also stuff you don’t.

— Like a streaming service. You pay for all the shows, but only watch some.

—Or a combination plate at a food court. You get a good price on the whole thing, even if you don’t eat everything.

Right. Clay figures that’s the only way to get the job done. In a spirit of a compromise. Here are the highlights of the bill:

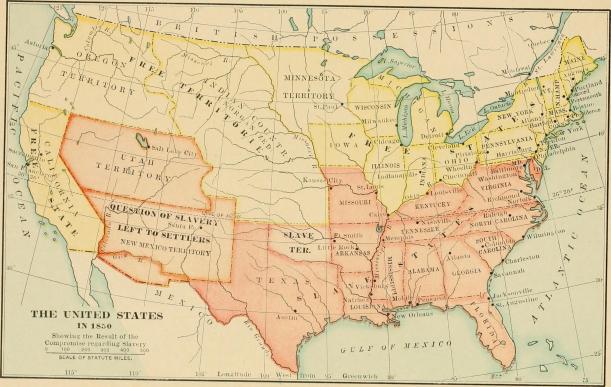

- California comes into the Union as a free state.

- The slave trade ends in Washington DC (a lot of people really hated the fact that slaves were bought and sold in the nation’s capital).

- There’s a new stronger fugitive slave law. I’ll talk about this in more detail later.

- Rather than decide now what will happen to the Utah and New Mexico territories (a whole bunch of future states there, but not for a long time—Arizona, for instance, doesn’t enter the Union until 1912—a new principle, known as “popular sovereignty” will be used to determine whether such states will be slave or free. The voters will choose rather than Congress deciding.

So, what do you think?

—The first two ideas seem to favor the North. The third one the South. The last one breaks even. So the overall law seems pro-Northern.

A reasonable assessment, Ethan. But point number three is a big one. Again, I don’t want to get into it right now. But suffice it to say that in Clay’s mind, at least, the overall package was truly balanced. What do you think, Sadie?

—Sounds reasonable. Does it work?

No.

—Oh. Why not?

Well, that’s complicated, by which I mean you ask ten people you’ll get ten different answers. I will tell you that old man John Calhoun, who had been at it as long as Henry Clay and was in fact on death’s door, told his fellow Southerners to reject the bill, and he had a lot of influence in the Senate. Senator Daniel Webster of Massachusetts—remember him? We talked about the big speech he gave, “Liberty and Union, now and forever” a while back—came out in favor of the bill, and got a lot of grief over it. Clay was known as “the Great Compromiser”—remember, he’s the guy who got the Compromise of 1820, a.k.a. the Missouri Compromise through Congress—but he just couldn’t summon the old magic.

—So what happened next?

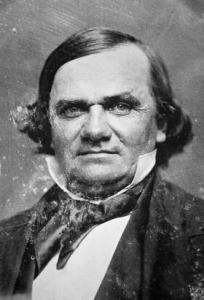

- Stephen A. Douglas

—How did he do that?

A very good question, Yin. The short answer is horse trading. So take the California piece for example. He’d go do you, a Southern senator, and say: Hey, I know you hate this bill. But if you pass it, I’ll make sure you get that bridge you want for your state. Or the railroad going through your town. That kind of thing. It was very complicated, and exhausting, but it worked. And before the year was over, President Millard Fillmore—the non-entity who followed the forgettable Zachary Taylor, who died a few weeks into office—signed the Compromise of 1850 into law.

—So what happened then?

Peace in our time, of course. Crisis averted.

—Well, we know that didn’t happen. So what went wrong? Who blew it?

Stephen A. Douglas did. But a few things had to happen before he could. We’ll get to them.

—Such drama!

All in a day’s work, kids.

The compromised compromise