In which we see how the man who broke the mold of the Founding Fathers became the scariest, and most exciting, man in U.S. history

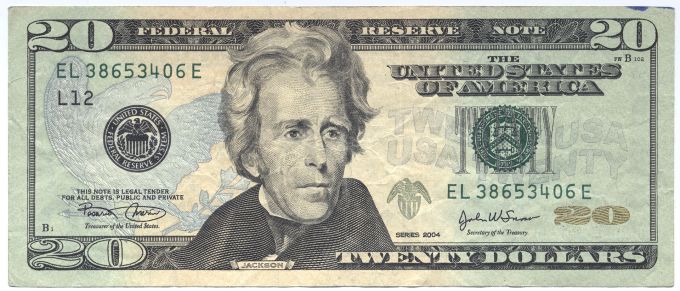

Did you all bring $20 bills? Hold them up.

—We’re going to get these back, right? My mom was worried.

Right, Ethan. Actually, I’m not collecting them. I just asked you to bring them today for a little exercise we’re going to do. Looks like a few of you don’t have one. That’s OK. You can share. Go ahead and put those bills on your desks. Now look at the figure in the middle of them. What do you see?

—Jackson.

Yes. That’s what it says: Andrew Jackson. Seventh president of the United States. But what I’m really asking is what you see. What do you make of this portrait?

—Great hair.

—It is great hair.

—Looks like he’s wearing a cape.

—Is that a white collar under his shirt? And is that a tie sticking out between the cape?

—They didn’t wear ties back then.

—Back when?

—When Jackson was president.

—When was that?

—I dunno. A 150 or so years ago.

How about his face? What do you see in his expression?

—He looks pretty serious.

—His lips are tight. What’s the expression? His lips are pursed.

—I’m having trouble reading his eyes. He’s staring off into the distance. But I can’t quite tell how he feels about what he’s seeing.

Well, now, that’s an interesting question, Yin. Wait a second; let me get over to the Smart Board. I’m going to call up someone else on U.S. currency—Alexander Hamilton.

—I like Jackson’s hair better.

—Yeah, but Hamilton is kind of hot.

—Oh, he is.

—He’s a bastard.

—Oh, Ethan.

—No, literally. His mother wasn’t married when he was born.

—Yeah, yeah, we know. The “oh” was “how lame.”

Sadie, how would you characterize Hamilton’s expression compared with Jackson’s?

—Hamilton seems a little nicer. His lips look more like he’s smiling.

And his eyes?

—He seems …kinder.

OK, though I’ll note that a lot of people thought Hamilton was a bastard … in a different sense of the term. Anyway, here’s Abraham Lincoln on the $5 bill. What about his expression?

—Well, he looks serious, too. But I see kindness in his eyes as well. His eyes are darker than Hamilton’s. Maybe that’s why he seems warmer.

But Jackson’s eyes are dark.

—Yeah, but they’re harder to read. Maybe they’re just plain harder.

I agree. A sense of mystery. And hardness. You know what his nickname was? “Old Hickory.” You know why? Because hickory is one of the hardest woods in the forest. When I look at this portrait, I hear Andrew Jackson speaking. And do you know what I hear him say?

—What?

“Don’t fuck with me.”

—Mr. Abraham King! I am shocked. Shocked!

Don’t tell on me, Em.

—Your secret is safe with me, Mr. K. Sadie here is another question. Those eyes! Those hard eyes! (Stop laughing, Sadie.) I think we may have to swear some kind of blood oath with every member of this class. Either that, or pay a bribe. I’m thinking 20 bucks apiece should do it.

You’re so kind, Em.

—Just trying to help out.

I appreciate that. Fortunately, I have an understanding with Dr. Devens about this. I’ve explained to her that I have a pedagogical purpose in using the term “Don’t fuck with me” in the context of Andrew Jackson. Fortunately, she charges less than I would have to pay all of you. (Just kidding.)

So why do I want to use the phrase “Don’t fuck with me” in regard to Andrew Jackson? As far as I know, Jackson himself never spoke these words, which I believe are of distinctly 20th century vintage. It’s because I think it captures the visceral power and appeal of Jackson in way 21st century adolescents can understand. Jackson was one of the dominant figures—perhaps more accurately, he was one of the most dominant personalities—in the 19th century United States. Maybe in U.S. history generally. He’s on his way out these days, and will soon be vanishing from the $20 bill. I hope we can talk a little about that. But first I want to explain the series of events that led to him being put on that bill in the first place.

You may remember we talked a little about Jackson already, when we did the War of 1812. Anybody recall that?

—He was the general at the Battle of New Orleans. Which the Americans won.

Good, Jonah. Anybody remember the rest of his background? No? Let me remind you—well, let me round out the picture a little bit. Jackson was born in Carolina (note I don’t specify North or South, because as far as I can tell no one knows; his family lived in the interior, near Georgia, where the borders weren’t clear) in 1767. Jackson’s father died a few weeks before he was born. He was nine years old at the time of the Declaration of Independence. As you may remember, the center of the action in the Revolutionary War shifted to the South in 1780, when Jackson was thirteen. He enlisted in a local militia with his brothers. One brother was killed in battle; Jackson and his other brother were captured and imprisoned, where they caught smallpox. Their mother managed to get them out, but his brother died soon after, and his mother perished tending to wounded soldiers shortly after the Battle of Yorktown. Jackson was now an orphan, and swore his hatred of the British for the rest of his life. He spent the rest of his childhood with two uncles, piecing together enough of an education to present himself as a country lawyer (there were no law schools in those days).

Jackson was a child of the American frontier, and among the first pioneers to settle what became Tennessee, the 15th state in the Union in 1796 (after Kentucky and Vermont followed the first 13 as a pair five years earlier). Jackson was one of the founders of the city of Memphis. I’m a little murky on the details of a lot of this, in part because I’m no Jackson scholar, but also because, well, there’s just plain a lot of murkiness surrounding this. Seems like there were deals, and threats, involving the Cherokee and Chickasaw Indians. Jackson soon became a major slaveholder as well.

Jackson may have been a lawyer and a businessman, but the work for which he was best known was as a soldier. He was a member of the Tennessee militia when the War of 1812 broke out. As was true of the Revolution, the War of 1812 had lots of political and military implications for U.S. relations with Native American people. Many Indians, sick of literally getting pushed around, saw the war as an opportunity. In 1813, a faction of the Creek Indians known as the Red Sticks, led by a chief named Red Eagle, massacred hundreds of white and black settlers at Fort Mims, near modern-day Mobile, Alabama. Jackson was charged with defeating the Red Sticks, and led U.S. forces to victory at the Battle of Horseshoe Bend in 1814. Though he let Red Eagle live, he imposed harsh terms on the Red Sticks. The Creeks had a term for him, “Jacksa Chula Harjo” which translates to, "Jackson, old and fierce.”

—Don’t fuck with me.

Exactly, Chris. From there, Jackson went to New Orleans, where he faced—and very soundly defeated—a larger British force that landed just after the Treaty of Ghent had been signed (but before news had crossed the ocean). The Brits described Jackson as “tough as hickory,” and the name stuck. Jackson became internationally famous.

—Don’t fuck with me, Great Britain.

You’ve got it. In the years that followed, tensions remained in the American southwest, by which I mean Georgia, Alabama, and the Florida panhandle, parts of which were claimed by the United States, though most of Florida belonged to Spain. There were multiracial, multinational, attacks back and forth borders. (By way of illustration, Jackson’s adversary Red Eagle was partly white, and I’ll remind you that the army that Jackson led in New Orleans was multiracial.) In 1817, Jackson was ordered to fight the Seminole Indians, who made raids across the Spanish Florida border, as well as preventing fugitive slaves from escaping to Florida. In retaliation for a Seminole attack, Jackson proceeded to flagrantly violate Spanish sovereignty in Florida, capturing the city of Pensacola and putting two Brits who had collaborated with the Seminole to death.

—Don’t fuck with me, Seminoles!

—Don’t fuck with me Spain! Protect your fucking border!

—Don’t fuck with me, Great Britain!

—We already said that.

—Don’t double fuck with me, Great Britain!

—This is getting to be a little much.

—Isn’t that the point?

It is, Em, though I will confess to some ambivalence in encouraging our loose tongues with my little Jackson slogan. All joking aside, Jackson’s brazen disregard of international law, not to mention basic humanitarian decency, is raising alarm in Washington. There are some members of the presidential administration of James Monroe, who succeeded James Madison after the War of 1812, who want Jackson to be punished for his transgressions. Monroe himself has been giving mixed signals on Jackson’s behavior. In what will be one of the great ironies of American history, though, Jackson has an influential champion: Secretary of State John Quincy Adams.

Let me take a minute here and talk about Adams. First of all, do you recognize the name?

—Is he related to John Adams? His son, maybe?

That’s right, Ethan. JQA, as he was known, was born in 1767, Just like Jackson. But while Jackson’s life was hardscrabble and violent, JQA’s childhood was positively aristocratic by comparison. The second child and oldest son of the formidable John and Abigail, JQA was a child prodigy. He was seven years old when his mother took him to witness the Battle of Bunker Hill in 1775. He was ten when his father took him to Paris as part of the American delegation seeking recognition from France (the ship that father and son sailed on was chased by the British). At 14, he was appointed to serve as a translator (to French, the language of diplomacy) on a mission to Russia. (He would later hang out with his friend, the Emperor Alexander I, when Napoleon invaded that country.) JQA worked as his father’s secretary before returning to the states to attend Harvard—afraid he was getting a little too refined, his parents wanted him to attend a local school—and train as a lawyer. President Washington appointed him as the U.S. ambassador to the Netherlands when he was still in his twenties. Over the course of the next twenty years, he held a series of posts, among them a professorship at Harvard and a seat as the United States Senator from Massachusetts. He turned down a slot on the Supreme Court. During the Monroe Administration, JQA was Secretary of State—a position that already long been regarded as a springboard to the presidency.

—You said Adams stood up for Jackson?

Well not quite in those words, Yin.

—Seems odd that a diplomat would defend Jackson’s behavior.

It is odd. But diplomats and politicians are often juggling multiple agendas, and Adams senses opportunity in Jackson’s behavior. American leaders had been trying for years to get Spain to sell Florida to the United States without success. But Spain’s grip on this piece of North American territory was insecure, as attested by the porousness of a border routinely crossed by Native Americans, runaway African Americans, and now Jackson himself. Adams positioned himself as good cop to Jackson’s bad cop: maybe you should sell Florida while you still can, before the situation gets out of hand and a loose cannon like Jackson does something we may all regret. The fruit of such negotiations is the Adams-Onis Treaty of 1819, in which Florida’s territory is finally transferred to the United States. Not that this pacifies the region. The U.S. army will continue fighting in Florida for the next quarter century, notably two more wars against the Seminoles and their great multiracial leader Osceola, who successfully resisted U.S. control until his capture in 1837, when he was taken despite a flag of truce.

—Is that how we get the University of Florida Seminoles?

It is, Jonah. And a county in Florida that’s named after Osceola.

—Where is that? Is it near Disneyworld?

Naturally, Kylie. In any event, JQA’s machinations in Florida were of a piece with his broader foreign policy agenda of enhancing U.S. standing in the Western Hemisphere generally. It was during the Monroe administration that the British government approached the United States and said, basically: “Hey: you don’t want other European powers reasserting themselves in the Americas and neither do we. We could make a statement to this effect, but it would look better if we did it together—Britain as the big kid on the block, and the United States as the little guy. What do you think?” It was Adams who framed the U.S. response for the Monroe Administration, which was for the United States to go ahead and make its statement on its own in what became known as the Monroe Doctrine, which said that the U.S. would regard any outside power coming into the region as an act of aggression requiring intervention. Since this stance suited Britain’s position in the region, it tacitly agreed—and lent its considerable naval power to make the Monroe Doctrine effective in a way the United States alone never could. It marked the rapprochement between the U.S. and Britain that would gradually strengthen over the course of the next century.

—What’s Andrew Jackson doing while all this is going on?

Getting ready to become president, Jonah.

—When is this?

1824.

—That’s when Jackson becomes president?

That’s not what I said.

—So when did he?

Stay tuned.

House work: the presidential election of 1824