In which we see a foolish war, and its less foolish legacy.

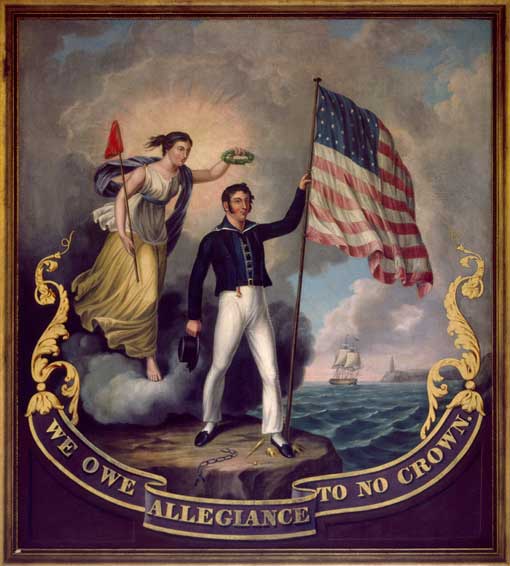

- John Archibald Woodside, "We Owe No Allegiance to No Crown" (1814)

England and France are at it again, kids. It’s been going on, more or less continuously, for almost twenty years now.

—When are we?

We’re in 1807, Jonah. Well into Thomas Jefferson’s second term.

—So easy to lose track of time.

When you’re having fun.

—Yeah, sure.

So it’s 1807, England and France are still fighting, and President Jefferson thinks he has a solution for the United States. Rather than take sides, or worry about getting caught in the middle, the United States should simply opt out. He backs the passage of the Embargo Act, which prohibits trade with England and France. Jefferson likes this law because it serves his domestic agenda as well: he wants the United States to be more self-sufficient. Developing internal trade is good economics as far as he’s concerned.

—Sounds reasonable. Does it work?

What Jefferson doesn’t quite get—or maybe what he doesn’t quite care about—is that shutting down trade is terrible for the New England economy. The United States is still in effect a British colony when it comes to pretty much any kind of manufactured good, and that’s not something that can be changed by a law. The region goes into a severe depression. New Englanders flout the Embargo Act, especially in terms of trade with Canada, which make the Jefferson administration mad but unable to do much about it.

Jefferson finishes his second term in 1809. His chosen successor is James Madison, who wins easily, notwithstanding the lack of votes he gets in New England. Madison, of course, has long been the architect of Jeffersonianism—he’s been the one to frame and implement Jefferson’s ideas—so his administration is one of continuity more than change. But that means dealing with a lot of the same problems, notably how do to deal with the ongoing problem of the Orders in Council, that British habit of pulling over American ships and forcing sailors to join the British navy. By this point, there are some new faces on the scene, like Representative John Calhoun of South Carolina, and Representative Henry Clay of Kentucky, who are pushing for a hard line with the British. They’re known as War Hawks.

The Madison administration stumbles along with this issue until 1812 (the year Madison is up for re-election, which he secures, on pretty much the same terms that had prevailed in 1800, 1804, and 1808), when the United States declares war on Great Britain. I call the War of 1812. The dumbest war in American history.

—Why?

I say so for a couple reasons, and the first is this: Britain had just agreed to stop the impressment (as it was known) of Americans, but the news didn’t reach Congress before the war broke out. So the two sides went to war even though the reason they went to war was no longer happening.

—You don’t hear much about the War of 1812. What happened with it?

Well, it was kind of a mess. The British were distracted by the ongoing fallout from the French Revolution, which had moved into a climactic phase: 1812 was the year Napoleon invaded Russia. The United States thought it could take advantage of this by invading Canada, a campaign that went poorly. Americans never understood that Canadians were just not interested in joining the United States. There was also a lot of naval warfare on the Great Lakes, which went relatively well. But overall, the first half of the war was pretty much a draw.

But then the situation abroad changed. Napoleon’s invasion of Russia was a disaster. He wrecked the French army, which was driven back to Paris. Napoleon himself was driven into exile. Now the Brits could really focus their attention on the United States. An invasion force was dispatched to Washington, and it wrecked the city (the White House was set on fire, and President Madison had to flee). The Americans managed to defend Baltimore, an event memorialized in the Star Spangled Banner, a set of lyrics written by Francis Scott Key that was set to a saloon song.

—Wow. That sounds pretty bad. How come we didn’t lose?

Here’s the thing: by 1814, Great Britain had been at war almost continuously for 25 years. The British public was exhausted. So the government decided to open negotiations with the Americans in the Belgian city of Ghent. There a deal was cut where the Brits agreed to do what they had already agreed to do: stop with the impressment of U.S. sailors. Which they didn’t need to do any more anyway. (Napoleon came back once more, and was defeated once more, at the Battle of Waterloo. But that happened later.) And so, in December of 1814, the Treaty of Ghent was signed.

Which brings us to one more dumb aspect of the War of 1812.

—Wait.

Yes, Adam?

—Were there many people who fought in the Revolution who fought in the War of 1812?

Not many. The two wars were almost 40 years apart, after all. But I can think of one person who was involved in both. He was a child when the Revolution happened. He saw his brother killed, and his mother died taking care of American soldiers on a prison ship. He himself was caught by the Brits, and when a British soldier told him to polish his boots, the kid in effect told him to you-know-what himself, he got slashed in the face with a scar he had for the rest of his life.

Now, in January of 1815, the kid has become an American general. He’s assembled a multiracial force—red, white, and black—to face a British invasion of New Orleans. None of these people has gotten word of the treaty, so the British proceed with the attack. And they are utterly crushed by the Americans. One of the greatest military victories in the nation’s history.

—What a waste.

Yeah, Sadie, it was, like I’ve been saying, kind of dumb. But it wasn’t necessarily a waste. Had the Americans lost, it’s easy to believe that the British would have tried to renegotiate the treaty. In any event, the Battle of New Orleans was a tremendous morale boost for the United States. It inaugurated a period known as the Era of Good Feelings, that would last for the rest of the decade. And it made that general, a man named Andrew Jackson, a force to be reckoned with in years to come.

The Battle of New Orleans was important for another reason as well. It really marked the end of this period I’m talking about when the United States was buffeted by stronger powers. From this point on, it would be more and more in control of its destiny. A new era was dawning.

—And another class is ending.

Go forth, young Americans.

Next: The Transportation Revolution