In which we see a crazy presidential election inaugurate a new chapter of American history.

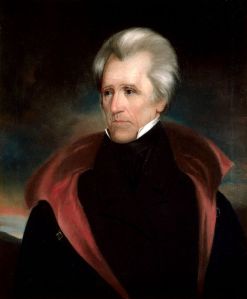

- Andrew Jackson

So here we are, kids, at the presidential election of 1824, and it’s shaping up to be like no other in American history. Up until this point, there have been a total of five presidents—Washington, Adams, Jefferson, Madison, and Monroe—and all of them, except Adams, had served two terms. All except Adams had been Virginians, too. In each case there was a sense that it was the given person’s turn, and while some elections had been contentious, the Founding Fathers had resisted casting their choice simply as a matter of politics and ideology: for them “party” was a four-letter word. By this logic, John Quincy Adams, or JQA, son of the second president, was next in line. He certainly thought so, and he certainly thought he should not have to fight for a job he very plausibly believed he was best qualified to fill.

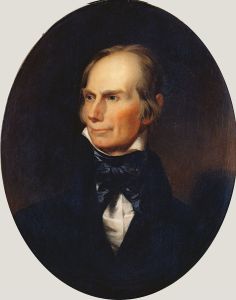

But the world was changing by 1824. Though the Federalists were spent as a political force in national politics, there were tensions in the old Jeffersonian Democratic-Republican coalition between generations (the younger crowd was generally more comfortable with a more assertive federal government). There were also new faces on the scene, like Henry Clay of Kentucky, and John Calhoun of South Carolina, the so-called War Hawks who had egged President Madison to declare the War of 1812. There was also William Crawford of Georgia, who would ultimately have to drop out of the race because he fell ill. None of these men were willing to simply defer to JQA.

And then there was Andrew Jackson. He wasn’t exactly a new face in 1824—he’d been a national celebrity for about a decade by that point—but he certainly was an outsider. This was true in a number of respects. For one thing, he was not a professional politician. For another, he was a man of the West, hailing from a state admitted to the Union after the Revolution. Jackson’s policy positions weren’t very clear, but that worked in his favor; his champions read what they wanted into him, and in any case saw him as a new and fresh voice.

So, what do you say, kids? Do we go with Jackson? Or Adams? Or maybe one of the other candidates?

—Tell us a little more about the other guys.

- John Calhoun

Well, Adam, I won’t bother with Crawford, since he withdrew. Calhoun is an interesting guy. At this point in his career, he’s a strong nationalist. But Calhoun is from South Carolina, which is a slave state, and, increasingly, a cotton state. The evolving cotton economy has strong ties to the national government (New York banks, for example, lend a lot to plantation owners trying to buy land, slaves, and equipment), but there’s also anxiety about the feds interfering with what they call their “peculiar institution.”

—What’s that?

Slavery. South Carolina, and the South generally, is literally and figuratively becoming ever more invested in it. And that’s affecting its stance on any number of other things. There’s a fear, for example, that giving the federal government the power to do anything in the economy might eventually legitimate its ability to regulate slavery. Calhoun will soon be drawn ever more tightly into the orbit of this slaveocracy, as it was known. But for now, he’s got his eye on the presidential prize. A famous observer at the time, Harriet Martineau, describes Calhoun as “the cast-iron man, who looks as if he had never been born and could never be extinguished.” But a little spoiler, here, kids: this isn’t Calhoun’s time. He will end up vice president, though, and that will prove very interesting.

—Sounds more like a teaser than a spoiler.

- Henry Clay

So be it. The guy I really want to talk about now, though, is Henry Clay. Clay, was born in Virginia but moved to Kentucky as a young man because he thought he’d have more opportunities on the frontier (it was Clay who coined the term “self-made man” to describe the widespread reality of upward mobility in the United States, of which he considered himself a prime specimen). Clay was the quintessential happy warrior. Nothing seemed to please him more than a worthy adversary and a good bottle of whiskey. His nicknames—“the gamester”; “Prince Hal”; “Great Harry of the West”—suggest his playfulness and informality. After serving in the Kentucky legislature, Clay was elected to finish the term of a Senator who left to take another job in 1806. No one seemed to notice, or at any rate mind, that Clay was only 29 years old, a few months shy of the Constitutionally mandated 30. What may be more amazing is that when Clay was elected to the House of Representatives in 1810, he instantly elected Speaker of the House. He was one popular guy.

There was more to Clay than that, though. He was Alexander Hamilton with social skills: a pragmatic visionary. Like Hamilton, he had a vision for his country that he called “the American System,” the details of which I’ll get into later. Suffice it for now to say that Hamilton was like Clay in his belief that manufacturing was the key to the nation’s economic future, as was a strong national government to stitch the nation together with things like roads and canals. The difference was that Hamilton was an avowed elitist; Clay couldn’t afford to be. Not in a country that was rapidly becoming one where any white man could cast a vote. That doesn’t sound like much to you, I know. That glass is half empty—maybe more like 2/3 or ¾ empty. But it was a big deal at the time.

Clay was a slaveholder. He also opposed slavery.

—How could that be?

People can be complicated, Sadie.

—About that? How could you be on both sides of that?

Ask Thomas Jefferson (who’s still around in 1824, by the way). Are you opposed to poverty?

—Of course.

Are you willing leave your home and give up your goods in the name of economic equality? Or to equalize funding for all school districts, which would mean this school is less good than it is now?

—That’s different.

Is it?

—Yes.

Let’s agree to disagree for the moment. Clay was a charter member of the American Colonization Society, which sought to buy freedom for slaves and send them send slaves back to Africa. An impractical idea that passed for philanthropy at the time. Jefferson was a member of that club, too.

—So they were racist.

Yes, Emily. And your epidermis is showing.

—What?

—He means your skin, Em.

Right, Adam. To call Henry Clay a racist is to state the ragingly obvious: virtually every white person in the 19th century was racist by our standards. Even abolitionists far more committed than Clay ever was to ending slavery sound painfully condescending. It was a different time with different standards for appropriate attitudes and conduct.

—Maybe so, Mr. K. But at least there were people out there against slavery trying to do the right thing.

Yes, there were, Sadie. And Clay was no saint. He was an ambitious guy trying to do and say what he needed to get elected, trying to find a majoritarian sweet spot in the middle of a road where the middle keeps moving. Which is to say that he was a politician. But people can be politicians in different ways, as we’ll see. Clay was a slaveholder. As was Calhoun, and Crawford, and Jackson. Adams wasn’t: the Adams family was relatively good on the slavery issue. So maybe he has your vote, then? There were certainly people—not a lot, but some—who favored him for that reason. A lot of them were women. But of course women couldn’t vote.

—Yeah, Adams gets my vote.

Fair enough. Any other takers? Raise your hands. Adam, I see we have you. And Em. And Brianna, Ethan, and Jonquil. Brianna and Chris. Looks like JQA wins this election.

—I don’t really get Jackson’s appeal.

Really, Yin? Why is that?

—Well, I get that he’s a soldier who’s won lots of battles. And that he’s new. But what was so great about him?

Let me tell you a little story that might help. Jackson had a wife, Rachel, whom he adored. She had been married. But her first husband left her and disappeared without a trace (not all that uncommon at the time). After a decent interval, she and Jackson married. But then her first husband, to whom she was still legally married, returned. Not a big deal: they worked it all out. But for a time, Jackson was technically a bigamist. There was a guy named Charles Dickinson who made fun of Jackson about this. So he challenged him to a duel.

—Naturally.

Right. You know the drill. Dickinson gets the first shot. He aims, fires, hits Jackson in the chest. And Jackson just stands there.

—Wait. Really? How can that be?

Now it’s Jackson’s turn. He coolly takes aim, fires, and kills Dickinson. Only then, after Dickinson is dead, does Jackson fall to the ground, injured: He wasn’t going to give that son of a bitch the satisfaction of knowing he was hurt. Jackson would carry that bullet around for the rest of his life.

—Don’t fuck with me, Dickinson.

You got it. Old Hickory: tough as nails. Such stories about Jackson were legendary. That help, Yin?

—I guess. Not really my thing. But I guess it would appeal to a lot of men at the time.

Exactly. Clay may have been likeable (maybe a little too likeable; there was sometimes a perception that Clay was on the slick side). But Jackson was thrillingly his own man, an embodiment of the rugged individualism that was emerging as a widespread ideal of the time. Anyway, the presidential election of 1824 was unusual from start to finish. After the votes came in, two things were clear: Jackson had the most popular votes, but he didn’t have enough votes in the Electoral College. Does anybody remember what happens in that case?

Anyone? Had it ever happened before?

—Oh yeah. With Jefferson.

Good, Jonah. Can you remember how that went?

—There was the whole Hamilton thing.

Right. But what does the Constitution say?

—There’s a vote in Congress.

Yes. In the House of Representatives. Each state delegation decides on a candidate. As you might imagine, the jockeying was intense. But when the dust settled, two things had happened: Adams won the Electoral College. And Clay was announced as the new Secretary of State.

—So they made a deal.

Oh no no no, Ethan. Not as far as the Jackson camp was concerned. This was no mere deal. It was a corrupt bargain. A massive fraud perpetrated on the American people.

—That seems a little much.

Yes, Sadie, it does. And it did then, to a lot of people. Certainly there was no law against a deal between Adams and Clay, and there had been many like it before and since. But the fact that Jackson had been deprived of the presidency despite winning a majority of the votes rankled a lot of people. Of course, it was precisely to stop people like him—people who might be massively popular, but also deeply troubling to the elites who run the country—that the Electoral College had been created for the first place. It was a circuit breaker, a device to prevent a dangerous power surge. It worked precisely as it was supposed to, much to the relief of Jefferson and Old Man Adams, who was approaching ninety years old. It was during JQA’s presidency, on July 4, 1826 that both Adams and Jefferson died.

—The same day!

Yes. Adams’s dying words were, “Jefferson survives.” (He’d died a few hours earlier.)

—So what happened after John Quincy Adams became president?

- John Quincy Adams

—Don’t fuck with me, John fucking Quincy fucking Adams!

Ahem. It was a new day in American politics. The inauguration of Jackson in 1829 was followed by a party of the kind the nation had never seen—by which I mean a frat party. Revelers wrecked the White House furniture. A gigantic wheel of cheese—

—Cheese?

Yup. A huge wheel of cheese was rolled up on the White House lawn. Jackson himself slipped out during the festivities. But the party raged on. And party, by the way, was no longer a four-letter word. Jackson fired all the old-timers in senior positions and brought in his own people, his so-called Kitchen Cabinet. From this point on, it became an accepted fact of American politics: a new administration meant jobs for a president’s supporters.

The question now was what Jackson was going to do now that he was in power. And on that count there were a lot of curious people. I hope you’re one of them. Because I’ve still got a few things to tell you.

Next: Shoe story